Making a podcast

Contents

Goals & excuses

A lot of podcasts release an almost unedited episode every week, but my goal was different. I wanted to hold each episode to the same standard as a conference talk: a useful, self-contained, properly constructed document of something interesting and unique.

I have no prior experience with audio recording or editing, so I’m painfully aware that I’m muddling my way through tools and processes that I don’t understand. But I find it interesting that the technology is forgiving enough to make it possible for me to produce such a thing, even if I’m getting every step wrong.

I’m also conscious that parts of this are more labour-intensive than necessary. Sometimes that’s because I’m being needlessly detail-oriented, and other times it’s because I’m doing a laborious task manually even though I know it can be automated but suspect that learning how would take even longer. This is frustrating but is also, I think, a normal part of the learning process for anything self-taught.

So none of this is advice, and this is not a tutorial; it’s just what I do when I’m trying my best at a hobby I know nothing about. If I receive any feedback from people who actually know what they’re doing, I’ll update this post to reflect it.

Starting up

I chose to invest a bit of money and time before recording an episode. Most of this wasn’t necessary — if you have access to a computer (or just a phone/tablet) you can make a podcast without any special equipment or preparation — but I wanted to make the quality as good as I could easily achieve, and that meant buying some extra stuff.

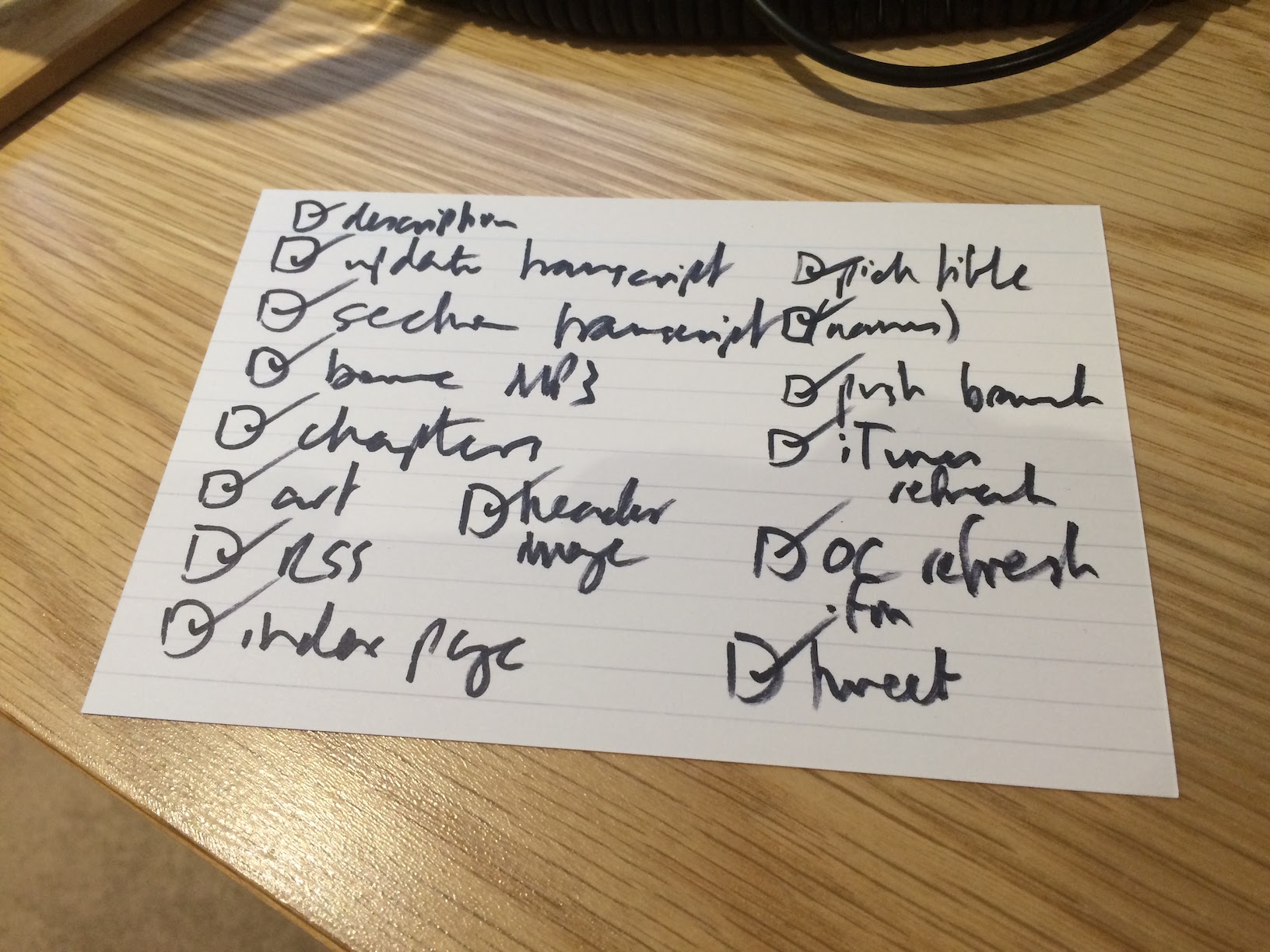

Here are all the jobs I can remember doing:

Get the hardware

- Zoom H4n digital recorder (£230). This has two built-in condenser microphones and two XLR inputs for connecting external microphones, and can either record directly onto an SD card or operate as a USB audio device. For the first episode I put batteries in it and used it as a standalone recorder; for the other episodes I used it as a USB-powered XLR interface to record onto my computer.

- Shure Beta 87A condenser vocal microphone (£225), Shure A85WS windscreen (£18) and Rode PSA1 boom arm (£70). I had no basis for choosing a microphone and accessories, so I picked these solely because they were what podcasting enthusiast Marco Arment recommended at the time.

- Wacom Intuos Pro medium graphics tablet (£250). I tried doing audio editing without this and got RSI almost instantly. It really helps.

- Fortunately I already owned a computer and headphones.

Get the software

- Audacity (free) for recording from microphones. Despite having a horrendous user interface, Audacity feels more robust and workmanlike than any of the fancier alternatives I tried. During recording, its status bar continually updates with an estimate of how much disk space is free and therefore how many more minutes of audio it can record, which gives the reassuring impression that it’s saving audio directly to disk and won’t lose anything if it crashes (which has never happened).

- Audio Hijack (£40) for recording Skype calls. I’d rather record in the same room as the guest but that's often impractical, so some episodes happen as a remote conversation over Skype, with each participant recording their own microphone separately (i.e. a double-ender). The Skype audio isn’t used in the final episode, but I record the call for two purposes: as a reference track for synchronising the separate microphone recordings, and as an emergency backup in case any recording fails (which also has never happened).

- Logic Pro X (£150) for editing. This is overkill — Logic is designed for professional music production — but I couldn’t find anything simpler that made multitrack non-linear audio editing bearable. Logic also makes it easy to assign hotkeys to common operations, which makes the editing process much quicker.

- Podcast Chapters (£15) for adding chapter markers to MP3s. Some podcast clients (e.g. Overcast) support these, and they’re handy for skipping around inside a long recording. It used to be possible to add chapters to AAC files with GarageBand, but that support has been removed in recent versions, and AAC “enhanced podcasts” seem to be waning in popularity anyway.

- iTunes (“free”) for adding ID3 metadata (title, description, cover art etc) to MP3s. There is probably a simpler way of doing this but I am lazy and know that iTunes works.

- VLC (free) for audio playback during transcription. I use VLC because I can control it with the Apple keyboard’s media keys, which makes it easier to play, pause and rewind audio without switching away from my text editor.

Register the domain

I registered whyarecomputers.com (£12/year) through Gandi.

Make a basic logo

I can’t draw, so I just took a photo of my computer. (Not literally “in the art room”, although it was at BERG, so that’s pretty close.) I ran the photo through an online image glitcher a few times to get several distorted frames, which I compiled into an animated logo with ImageMagick.

Make a basic site

I wrote static HTML and CSS by hand. I already had a nice webfont from Cloud.typography for codon.com, so I used that. And I already had a Linode VPS for codon.com, so I hosted the site there.

Make theme music

It seemed important to have a little bit of music to break up all the talking and provide continuity between episodes. I can’t write music, so I asked my talented friend Martin to do it.

Make a Twitter account

I created the @whyarecomputers account for announcing new episodes.

Recording the episode

Every episode begins as an unedited recording of a conversation. Getting to that point is the least time-consuming part of the process, but there is a bit of work involved:

Find a guest

This isn’t active work, but it takes forever because my technique is to do nothing and wait for someone good to fall into my lap. For example, almost three years elapsed between episode 1 and episode 2 while I waited for a suitable guest to materialise.

Once I’ve decided on a guest, I contact them and persuade them to come on the show.

Organise a venue if necessary

I try to arrange for us to record in person if that’s practical, because in-person conversations are more relaxed and natural than Skype calls. They’re also easier to edit because the low latency reduces the risk of people talking over each other. (Spill is a downside.)

To record together we need a venue that’s comfortable, quiet and not too echoey. For episode 1 we used the now-defunct Makeshift Shedscraper, and episode 4 was recorded at my flat in Hackney.

Schedule the recording

I want the finished episode to be roughly an hour long. When scheduling the recording I build in lots of slack time for unrushed pre-show warm-up chat, technical difficulty resolution, digressions, breaks, and post-show wind-down chat. A total of two hours is ideal.

I live in London, so scheduling Skype calls with guests in North America can be difficult. The obvious solution is for me to be flexible; episode 2 was recorded from midnight to 2am London time.

Prepare the guest

The guest may have no idea what to expect, so it’s important to proactively tell them anything they need to know rather than wait for them to ask.

If the guest is remote, I ask them to record the audio from their microphone and give them instructions if necessary. I can’t control the quality of the microphone they use, but getting a clean recording from it can at least eliminate Skype-related audio problems.

I also ask remote guests to take a photo of themselves in their recording environment, because I can't take one myself. I’ll use this later to make a header image for the episode page.

Being recorded for an audience is intimidating. I reassure the guest by telling them that:

- it’s safe for them to relax and speak freely, because the point of the podcast is to produce something entertaining that shows them in the best possible light, not to authentically document reality;

- it’s my job to guide the conversation, so they don’t need to prepare topics or worry about running out of things to say;

- if they stumble, misspeak, lose their train of thought or run out of steam, I’ll clean it up later in the edit; and

- if they want to start again or take something back, they can say “I’ll say that again” or “scratch that” and I’ll clean it up.

Prepare myself

This is the first time-consuming task. My primary contribution to the podcast is to have a rough idea of what is going to happen so that the guest can relax and not worry about it.

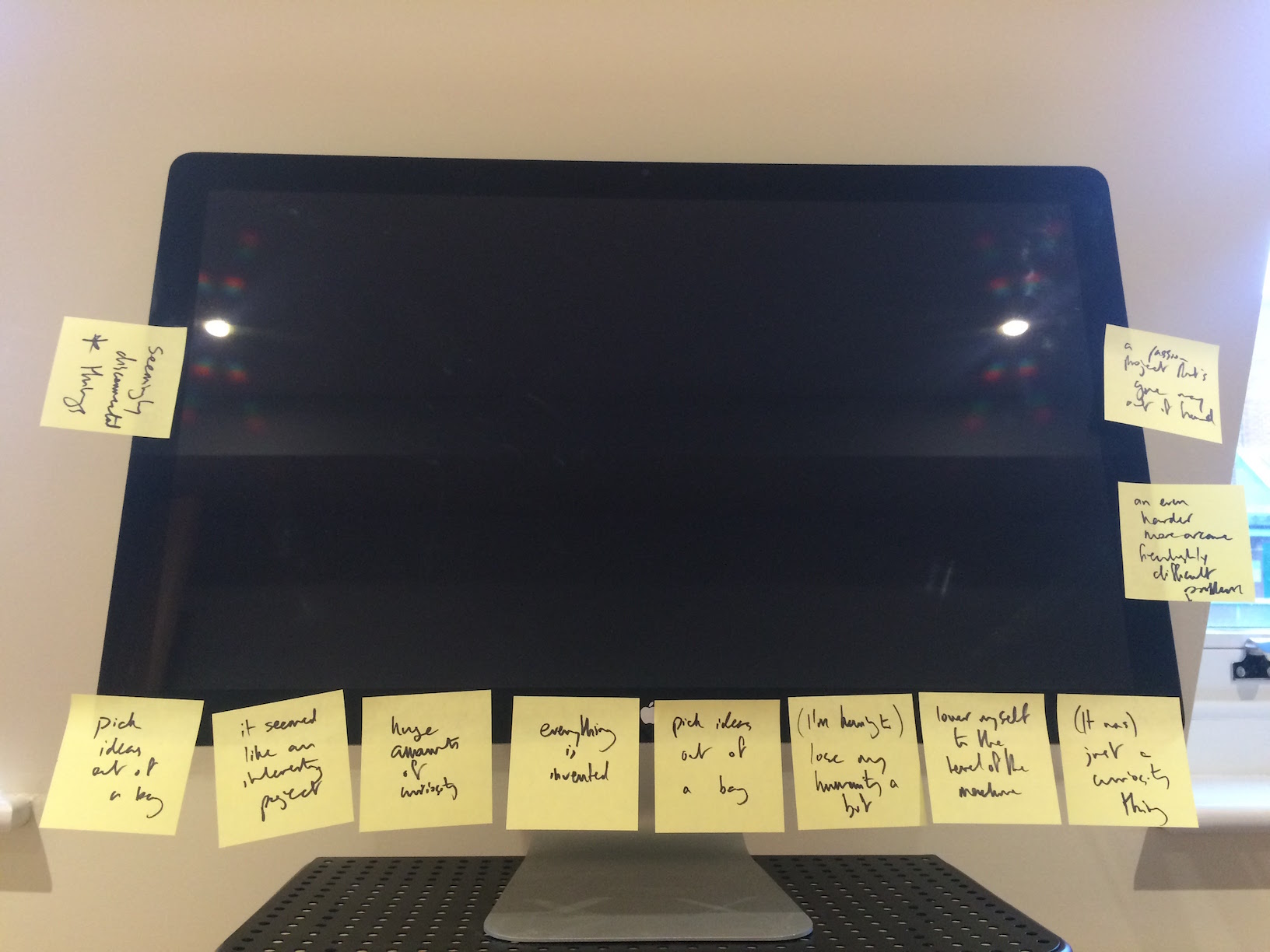

The more I prepare in advance, the less effort is required during recording. I want the conversation to flow naturally, but ideas chosen at leisure tend to be better than those which occur in the moment, so I like to have the overall structure in mind before we begin. A solid plan creates a more inviting space for spontaneity.

I read about what the guest has done. I already know a bit about them, but I run through their site, blog or Twitter feed and make sure I’m properly aware of everything they’ve said or made recently. I think about everything I’ve found. I take notes about what to ask them and what to say. I look for themes in their work and decide which ones to steer them towards. I look for topics that fit together to make a rough narrative.

Although I would rather have a conversation than an interview, I write straightforward questions as a fallback in case the conversation tails off naturally.

I also write what I’m going to say in the introduction. “Write” is a bit grand — the intro tends to be a combination of boilerplate and facetious nonsense — but it’s better for the guest’s confidence if I begin with something I’ve finalised beforehand rather than a half-hearted ad-lib.

Do the recording

As above, I record with Audacity on my computer. If we’re on Skype, I ask them to do the same (or use QuickTime Player if they prefer) while I record both ends of the call with Audio Hijack for sync and backup purposes.

If the guest joins me in person, I take a photo of them to use as a header image.

I split the recording time between general chat to make us both feel comfortable, and asking questions to get them to talk about specific topics. (Only the latter ends up in the episode.)

Making the MP3 and transcript

Once the recordings have been made, I have to turn them into a finished episode that I can release. This takes the most time by far.

Edit 1: noise removal

The goal of the first edit is to gather all the audio tracks and remove background noise from them.

If the guest recorded themselves, I ask them to send me their audio; if I recorded two microphones myself as a single stereo track, I use Audacity’s “Stereo track to Mono” to split it into separate mono tracks first.

I open each track in Audacity, use the noise profiler to analyse a section that is just background noise, then use the noise reduction tool to remove that noise from the entire track. I export each track from Audacity as a mono WAV, and that’s the last time Audacity is involved.

(I expect Logic Pro X can do better noise reduction than Audacity, but I don’t know how.)

Edit 2: raw

The goal of this edit is to make a single audio file that I can transcribe.

I make a new Logic project and import each speaker’s audio as a separate track.

If the tracks were recorded separately, the first job is to sync them up. Unfortunately this is more difficult than just synchronising them at the beginning, because audio recorded simultaneously on different computers will run at slightly different speeds and gradually drift out of sync. The effect is tiny but becomes significant after an hour or two of cumulative drift.

To fix this, I import the reference audio from the Skype call and use it to manually line up the other tracks at the beginning of the recording. I then skip to the end and use Logic’s time stretch to make each track longer or shorter so that it matches the reference track. This is fiddly and imprecise — and slow, because it takes Logic a long time to re-render the stretched region before I can check it sounds good — but after a few tries I can usually reduce the drift to an acceptable level. Getting it right was especially challenging for episode 3, which had two remote guests. I delete the Skype track once the sync is fixed.

(Marco Arment has written a tool called Sidetrack that fixes drift automatically by splitting tracks at silence and moving them around to match the reference track, but he hasn’t released it yet.)

Once the tracks are synced, I cut off any chat from the beginning and end that is unlikely to make it into the final episode. I pan each track to a slightly different place in the stereo image (usually me at -16 and the guest at +16), adjust the gain of each so that they roughly match, and add noise gates to filter out intermittent noises.

I finish by bouncing the whole project as a stereo WAV.

Transcribe

I transcribe the raw edit as a plain text file. Making a transcript takes a long time, but it’s important for two reasons:

- untranscribed podcasts are inaccessible to the hard of hearing, people who work in offices without headphones, people who don’t have time to listen to audio, people who don’t enjoy listening to audio, screen readers, search engines, etc; and

- text is much easier for me to review than raw audio.

I play the raw edit in VLC, pausing and rewinding it with my keyboard’s media keys while I type words into Vim. This is fairly frustrating because it’s easy to hit the wrong key and lose the playback position, but I don’t know a better tool for it.

At this stage I don’t waste any time on formatting or links, although I do note changes of speaker by starting a new line with their initials (e.g. “TS:”).

Read and think

Until now I won’t have spent any time reflecting on the conversation. The recording itself passes in a bit of a blur, and when I’m transcribing I pay attention to individual words rather than the conversation’s content or large-scale structure.

So now I read the transcript properly. The main goal is to make all the editorial decisions about which parts of the recording I’m going to keep and what order they’re going to go in; a secondary goal is to collect other bits of information that will be useful later.

I think about topics and themes, and take notes about which sections to rearrange or remove entirely to improve pacing and focus. I often backtrack on those decisions when an apparently irrelevant digression turns out to become useful later on. Fortunately it’s much easier to spot structural issues in text than in audio.

While I’m at it, I note down interesting phrases that could serve as either the episode title or the quote I include in the announcement tweet.

I also take notes about sections that could become self-contained chapters within the episode, and make a list of outtakes that could be used as a funny cold open.

Edit 3: rough

The goal of this edit is to finish the speech parts of the episode. This is the main editing job, and is extremely time consuming.

I play through the recording in Logic from beginning to end, editing as I go. I make large structural edits according to my notes from the transcript: removing and rearranging sections for pacing and focus, removing my prompts and comments as much as possible, and closing big gaps due to breaks or smalltalk.

I also make a huge number of tiny manual edits, for which the Wacom tablet is pretty much essential:

- remove silence when the speaker isn’t speaking (sidechain compression would do this automatically but I can’t get it working right);

- adjust region gain to make quiet speech audible and loud noises less abrasive;

- remove breathing sounds, lip smacking, sniffing, coughing, swallowing, clicks and pops;

- remove “um”, “er”, “so”, “like”, “kind of” (I find this very hard — occasionally the removal is perfect, but often it’s impossible for me to conceal the edit point); and

- remove unnecessary words and sentences, pauses for thought, false starts, and people talking over each other (these are all easier to remove).

The pointlessly meticulous process of making this rough edit takes days and is exhausting, so I usually have a break before I carry on.

Update transcript

Now the transcript is out of date, so I listen back to the rough edit and update the transcript as I go. Since this version of the transcript should be final, I also take the opportunity to add some HTML (mostly paragraphs and links), expand the speaker initials into names, and put section breaks where the chapter boundaries will be.

This listen-through always catches several problems with the audio or the original transcription or both, so I flip between Logic and Vim to fix things as I listen.

Edit 4: final

Once the transcript matches the rough edit, I put the final pieces of polish on the audio. I add the cold open, the intro and outro music, and the musical breaks between the chapters.

I bounce the finished project as an MP3, and that’s the last time Logic is involved.

Add metadata

The audio is now finished, but the MP3 needs appropriate ID3 metadata so that it shows up correctly in podcast clients.

I pick a final title from the interesting phrases I noted during transcripton, write a description for the episode, and come up with descriptive titles for each of the chapters.

I import the MP3 into Podcast Chapters, add the chapter times and names, and export the file again.

Then I import it into iTunes, open the “Get Info” view, and add the rest of the metadata (cover art, title, description, artist, genre, track number). By using “Show in Finder” I find the underlying MP3 file and copy it out of my iTunes library into the Git repository for the whyarecomputers.com site.

Publishing the episode

All that remains is to actually release the episode to the world. Unsurprisingly this involves a few little jobs, mostly because for some reason I maintain the whyarecomputers.com site by hand rather than use a CMS.

Make the episode page

The new episode gets its own page on whyarecomputers.com. I copy the HTML and CSS from the previous episode’s page and remove all the content, leaving only the boilerplate and empty structure.

Embed the MP3 into the episode page

Although it’s not the ideal way to listen to a podcast, I want anyone who lands on the episode page to be able to start playing the audio immediately in their browser. I put a simple <audio> tag in the page and point it at the MP3, which is enough to make browsers show a simple inline audio player.

Add title and description to the episode page

I’ve already picked a title and written a description for the ID3 metadata, so I paste those into the episode page, adding HTML (i.e. links) if necessary.

Add title and description to the front page

I have to remember to add an entry on the site’s front page too, so that people can find the new episode from there.

Update navigation on the previous episode’s page

Each episode page has “previous” and “next” links, so when a new episode is released, I add a “next” link to the previous episode’s page.

Update the RSS feed

The site’s RSS feed is what podcast aggregators use to discover the new episode and notify subscribers about it, so it’s very important to get this right. I add a new entry containing the episode’s title, description, publication time and file size.

Validate the RSS feed

To check I haven’t made any mistakes while hand-editing the RSS feed, I run it through the Feed Validator. This is stricter about correctness than any podcast aggregator I know, so I tend to ignore its more pedantic warnings, but it lets me see immediately whether I’ve made any serious errors.

Add a header image to the episode page

I scale and crop the photo of the guest and add it to the top of the episode page.

Add the transcript to the episode page

Once everything else is ready, the transcript makes up the bulk of the content on the page.

Add chapter titles, links and metadata to the episode page

This is a general finishing-up pass. I add the chapter titles to the transcript and link to them from the table of contents. At the top of the page I add an MP3 download link, subscription links to the RSS feed and iTunes page, links to my and the guest’s Twitter accounts or home pages, a music credit and link, the publication time and recording date, and contact links for Twitter and email.

Publish site changes

The whyarecomputers.com site lives in a Git repository on my local machine, so publishing it is a simple git push web master.

Refresh the iTunes feed

For the very first episode, I used Apple’s Podcasts Connect to submit the podcast to the iTunes Store. I couldn’t do this any earlier because Apple requires an RSS feed containing at least one episode in order to create a listing for the podcast.

For each subsequent episode, I just log into Podcasts Connect and press the “Refresh Feed” button to tell Apple to check the RSS feed. (Doubtless this would happen automatically on some kind of schedule, but I like to proactively trigger it.)

I also habitually check the Overcast directory page for the podcast to check that the new episode is showing up there. I don’t think this does anything, but it gives me confidence that everything is working.

Tweet about it

I pick another quote from the episode and tweet it from the @whyarecomputers account with a link to the episode page. I usually wait a day or two to retweet this announcement from my personal account to reduce the chances of people missing it.

The end

And that’s it! Until the next guest occurs to me…

Conclusion

Thanks for reading all this. I hope you enjoy the podcast — despite the above, I do really enjoy making it and feel privileged that people take the time to listen.

If you’d like to support this ridiculous project or encourage me to make more episodes, by far the most helpful thing would be to rate or review it on iTunes, because that’s how random people on the internet find podcasts. Or just tell your friends!